How to calculate the Target Price for shares: How to interpret it

In the world of investing, few concepts are as frequently cited—and as frequently misunderstood—as the target price of a stock.

If you’ve ever read a financial report or an equity research note, chances are you’ve come across statements like “Goldman Sachs raises Apple’s target price to $210” or “Morgan Stanley cuts Tesla’s price target to $160.”

But what does that actually mean? Is it a prediction? A buy recommendation?…

Let me walk you through how I view target prices: how analysts arrive at them, the methodologies they use, and—most importantly—how you, as an investor, should interpret them to make informed decisions and avoid common pitfalls.

What Is a Target Price?

The target price is an estimate of a stock’s future value, typically over a 6 to 12-month horizon, based on the assumptions an analyst makes about the company’s performance and the broader economic environment.

In essence, it’s what the analyst believes the stock should be worth if everything unfolds as expected.

But here’s the caveat: a target price is neither a promise nor an exact prediction.

It’s the outcome of a financial model based on assumptions that may or may not materialise.

Ultimately, it’s just one tool—valuable, yes, but only when understood in its proper context.

How Is a Target Price Calculated?

Analysts rely on financial models and valuation techniques to estimate a company’s future value.

There are two widely used approaches to derive a target price:

1. Relative Valuation

This method involves comparing a company to its industry peers using valuation multiples such as:

P/E (Price-to-Earnings)

P/S (Price-to-Sales)

P/B (Price-to-Book)

EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value to EBITDA)

Formula:

Price Target = Projected EPS × Expected P/E Ratio sector

Example:

Suppose a company has a projected EPS (Earnings Per Share) of $2.50 and the sector average P/E ratio is 40.

Target Price: 2.50 × 40 = $100

This approach assumes the market will value the company similarly to its peers, which may or may not be justified depending on its quality, growth prospects, and competitive positioning.

2. Absolute Valuation

This is where the well-known Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model comes into play.

This method estimates the present value of a company based on the future cash flows it is expected to generate.

Formula:

Absolute Value of business = CF1/(1+r)1 + CF2/(1+r)2 + … + CFn/(1+r)n + Terminal Value/(1+r)n

Where:

CFx = expected free cash flow in year x

r = discount rate (reflects the business risk)

n = number of years projected

Cash flows are forecasted over 5 or 10 years, then a terminal value is added to represent value beyond that period. The sum is divided by the number of shares outstanding to arrive at the target price per share.

Other Factors Analysts Consider

Beyond valuation models, analysts also factor in:

Quarterly earnings results

Corporate events (mergers, acquisitions, leadership changes)

Macroeconomic conditions (interest rates, inflation, economic cycles)

Market sentiment and institutional interest

Sector trends

All of these shape the analyst’s judgement and may lead them to adjust the target price up or down.

How to Interpret a Target Price

Understanding a price target can help identify opportunities—or risks—but it requires nuance.

Here are a few key tips:

1. Compare It to the Current Price

If the target price is significantly above the current market price: potential upside.

If it’s below: it might signal overvaluation or trouble ahead.

Example: If a stock is trading at $40 and the target is $55, there’s a 37.5% potential upside.

But if it’s trading at $65 and the target is $55, it might be overvalued.

2. Check the Analyst Consensus

Relying on a single analyst’s view can be risky. Better to look at the consensus target price—the average across multiple analysts—to filter out personal biases.

3. Consider the Target Range

Some analysts provide a range instead of a single figure (e.g. $70–$85), reflecting uncertainty in their assumptions. The wider the range, the greater the uncertainty.

4. Watch for Revisions

Upward or downward revisions in a target price suggest the analyst’s view has changed, often due to:

Earnings revisions

New information

Shifts in the macro outlook

5. Contextualise the Recommendation

Target prices usually come with a rating:

Buy – expected to outperform

Hold – neutral

Sell – expected to underperform

Without that rating, a target price on its own lacks context.

A Step-by-Step Example

Here’s a real-world case using relative valuation.

Company: American Airlines

Share Price: $9.46

P/E Ratio: 7.61

EPS (TTM): $1.24

5-Year EPS Growth Rate: 20%

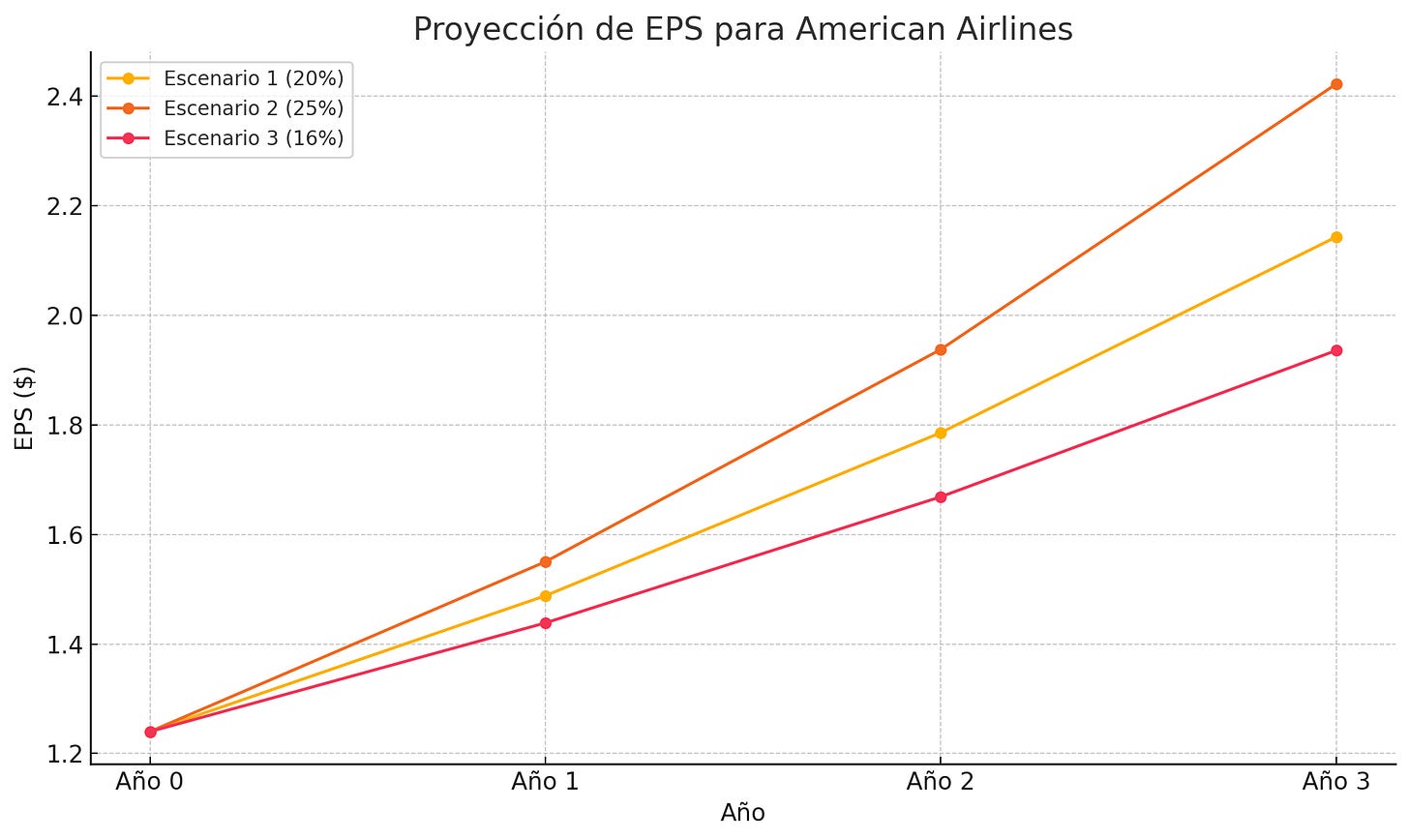

Scenario 1: 20% Annual EPS Growth

Year 1: $1.24 × 1.20 = $1.49

Year 2: $1.49 × 1.20 = $1.79

Year 3: $1.79 × 1.20 = $2.15

Target Price = 7.61 × 2.15 = $16.37

Scenario 2: 25% Annual Growth

Year 1: $1.24 × 1.25 = $1.55

Year 2: $1.55 × 1.25 = $1.93

Year 3: $1.93 × 1.25 = $2.42

Target Price = 7.61 × 2.42 = $18.43

Scenario 3: 15% Annual Growth

Year 1: $1.24 × 1.15 = $1.42

Year 2: $1.42 × 1.15 = $1.63

Year 3: $1.63 × 1.15 = $1.88

Target Price = 7.61 × 1.88 = $14.34

I always try to work with at least three scenarios when possible. It helps refine the estimate, especially when new data becomes available.

Pro Tip: As a subscriber, you gain access to the Tracking Sheet, a powerful tool for monitoring these valuations and tracking your own investment ideas. It’s genuinely high value for a ridiculously low cost.

And yes, while this is all maths and models—it’s still a helpful way to define cash-out strategies or make decisions based on your investment horizon.

Limitations to Keep in Mind

Even though target prices are useful, they come with caveats:

Markets can take time to reflect intrinsic value.

External shocks—political, regulatory, liquidity-related—can derail projections.

Assumptions might simply not hold up.

That’s why most investors treat price targets as just one tool in their decision-making toolbox—not the foundation.

Wrap-Up

Understanding and calculating a target price can be a powerful exercise—when done right.

We don’t have a crystal ball, of course. But this approach can help you better assess a stock’s value, making you more confident in when to buy, hold, or sell.

Whether you’re leaning on relative multiples or DCF valuations, knowing how that final number was derived will improve the quality of your decisions.

Just remember: the goal isn’t to guess the next resistance level to the cent—it’s to have a reliable reference point for when to take profit or stick to your plan.

And if you’ve made it this far—and you feel aligned with this mindset—you’re more than welcome to join our private investing community.

We’re already a solid group following the Portfolio360 strategy.

Your annual subscription includes:

Access to the Portfolio360 and its management

Entry into our private community

In-depth asset analysis (stocks, ETFs, crypto)

Full access to all Substack content

Live voice chats (one of our community’s favourite features)

Podcasts (past and future episodes)

Cash-in/out strategy guides

Personalised 1:1 sessions

Hope to see you there!